What is Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR)

Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) is not a traditional talk-therapy like most other psychotherapies.

EMDR is a psychotherapy that enables people to heal from the symptoms and emotional distress that are the result of disturbing life experiences. It is widely assumed that severe emotional pain requires a long time to heal. EMDR therapy shows that the mind can in fact heal from psychological trauma much as the body recovers from physical trauma.

What is the theoretical basis for EMDR therapy?

Unprocessed memories and feelings are stored in the limbic system of the brain and can be triggered when experiencing events similar to the difficult experiences an individual has gone through. The memory itself is often forgotten but the painful feelings such as panic, anger despair and anxiety are being triggered in the present time. EMDR helps to create connections between the brain’s memory networks enabling the brain to process a painful memory in a natural way.

How?

When you cut your hand, your body works to close the wound. If a foreign object or repeated injury irritates the wound, it festers and causes pain. Once the block is removed, healing resumes. EMDR therapy demonstrates that a similar sequence of events occurs with mental processes. The brain’s information processing system naturally moves toward mental health. If the system is blocked or imbalanced by the impact of a disturbing event, the emotional wound festers and can cause intense suffering. Once the block is removed, healing resumes. Using the detailed protocols and procedures learned in EMDR training sessions, clinicians help clients activate their natural healing processes.

What can I expect with EMDR therapy, i.e., what should/could happen?

Each person is different, but there is a standard eight-phase approach that each clinician should follow. This includes taking a complete history, preparing the client, identifying targets and their components, actively processing the past, present and future aspects, and on-going evaluation.

The processing of a target includes the use of dual stimulation (eye movements, taps, tones) while the client concentrates on various aspects. After each set of movements, the client briefly describes to the clinician what s/he experienced.

At the end of each session, the client should use the techniques s/he has been taught by the clinician in order to leave the session feeling in control and empowered. At the end of EMDR therapy, previously disturbing memories and present situations should no longer be problematic, and new healthy responses should be the norm.

A full description of multiple cases is available in the book Past Your Past: Take Control of Your Life with Self-Help Techniques from EMDR Therapy by Shapiro.

EMDR FAQs and Information

EMDR therapy is recognized as effective trauma treatment and recommended worldwide in the practice guidelines of both domestic and international organisations.

Yes, I sometimes prefer to treat phobias with EMDR because it requires less equipment, takes less time, and is easier to do when the phobia involves something difficult to generate in the therapy room, like an aeroplane flight, a public speaking engagement, or a large animal. In therapy, I will ask you to identify the first time you had an encounter with the phobic object or situation, as well as the worst time, and the most recent time. You will work through each of these situations, and an imagined situation in which you encounter it in the future. After this, you will be given an opportunity to test the resolution by engaging with the phobic object outside of the session to ensure that your phobia is resolved.

No. Two studies (Lee, Gavriel, Drummond, Richards, & Greenwald, 2002; Rothbaum, 1997) have indicated an elimination of diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in 83-90% of civilian participants after four to seven sessions. Other studies using participants with PTSD (e.g. Ironson, Freund, Strauss, & Williams, 2002; Scheck, Schaeffer, & Gillette, 1998; S. A. Wilson, Becker, & Tinker, 1995) have found significant decreases in a wide range of symptoms after three-four sessions. The only randomized study (Carlson, Chemtob, Rusnak, Hedlund, & Muraoka, 1998) of combat veterans to address the multiple traumas of this population reported that 12 sessions of treatment resulted in a 77% elimination of PTSD. Clients with multiple traumas and/or complex histories of childhood abuse, neglect, and poor attachment may require more extensive therapy, including substantial preparatory work in phase two of EMDR (Korn & Leeds, 2002; Maxfield & Hyer, 2002; Shapiro, 2001, 2018).

The type of problem, severity and amount of trauma, and life circumstances are factors that may affect how many treatment sessions would be required. In my practice, clients may choose to use only EMDR as a primary source of treatment, or to integrate EMDR into their regular sessions of talk therapy.

Healing is not an act, not something to be done, but a state to be entered into. It is a subtle dance between the mind and the body, a process of allowing the forces within us to come into alignment. We are constantly in flux, moving from past to present, from sorrow to joy, from brokenness to wholeness. And yet, how often we fight this natural flow, clinging to our pain, resisting the very process that could bring us peace.

EMDR—Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing—is not a cure in the traditional sense. It is not about eradicating something that is broken. Rather, it is about creating the conditions where healing can naturally take place. You see, the body and mind are not separate, they are one. When the mind is at ease, the body follows, and vice versa. EMDR is a process that allows this deep, symbiotic connection to come to the surface.

Let us begin with the History & Treatment Planning phase. This is not just about gathering information, it is about understanding the story—the narrative we’ve told ourselves for so long. Each of us carries a story, sometimes clear, sometimes blurry, but always powerful. It shapes how we see the world and how we see ourselves. The therapist in EMDR does not seek to rewrite this story but to help you see it with new eyes, eyes that are no longer clouded by fear or shame. The past is not something to escape; it is simply something to understand, to allow to dissolve in the light of awareness.

Then comes Preparation for Processing, which is a beautiful invitation to relax into the experience. You must first learn to let go of the need to control, to feel that you must always be in charge. This phase is about teaching you to surrender—not to others, but to your own inner wisdom. It is about trusting that you know how to heal, even if you don't have all the answers right now.

The Assessment phase follows. Here, you begin to identify the moments that still carry weight, the memories that have not yet been fully processed. But understand this: there is no rush. You don’t need to fix anything, you just need to bring awareness to what is. In this moment of recognition, you begin to understand the roots of your distress. And as soon as you see the root, you are already halfway to freedom.

Then, in the Desensitization phase, the real magic happens. The trauma, the fear, the anxiety, it begins to loosen. But how? Not through force, not through pushing. It is through gentle, rhythmic movement—like a soft wind that gradually changes the shape of a tree. With each movement, you release a little more of the hold the trauma has over you. It is as though you are not erasing the past, but simply allowing it to become distant, to lose its power over your present self.

Next, we move into Installation—the installation of new beliefs. But do not mistake this for mere positive thinking. It is not about replacing one thought with another; it is about creating space for something new to grow. Positive beliefs do not enter into a vacuum—they are planted in the soil of your experience, watered by the wisdom of your heart. This is not intellectual, it is a deep knowing that comes when you stop resisting and simply let things be as they are.

The Body Scan phase is perhaps the most subtle, yet most profound. Here, you are invited to reconnect with your body, to notice where the tension still resides. It is through this body awareness that you truly begin to release what has been stored, hidden, held tight. In this phase, you are not trying to force anything. You are simply becoming present with the body, allowing it to tell you where it still holds on to the past. With every gentle release, you move closer to total freedom.

In Closure, we return to calm. We pause, reflect, and integrate. We acknowledge that healing is a process, not an event. It is the art of returning to a state of balance, a state of wholeness, over and over again. Every step of the way is an invitation to be kind to yourself, to allow healing to unfold without resistance.

And finally, Re-Evaluation. This is not an end but a new beginning. As you reflect on the work you have done, you may find that new memories emerge, new emotions arise. This is the beauty of life—the journey is never complete. But with each step, you move closer to your true self, to the essence of who you are beyond all the stories you have told yourself.

EMDR is not a method of curing. It is a method of allowing. Allow yourself to heal, not through effort, but through surrender. When you cease fighting, when you stop running from the past, healing will find you. It is already within you, waiting for you to notice, waiting for you to let go.

Photo by Cash Macanaya on Unsplash

In physics, time and space were once seen as the great absolutes: unmoving, universal, the silent stage upon which life and matter unfolded. But then came Einstein, folding them into one another. And then came the poets of science — theorists like Carlo Rovelli, who tells us that time may be more fundamental than space itself. That space is not a thing we move through, but a relationship between events, a pattern of connection, an unfolding order.

“The world is not a collection of things,” Rovelli writes, “it is a collection of events.”

— The Order of Time (2018)

And if this is true — not only cosmically, but psychologically — what then trauma?

Because we are not just creatures of biology. We are temporal beings. Our thoughts stretch forward and back. Our memories live not only in the past but in the muscles, in the breath, in the tone of voice we use when we speak to ourselves. And when trauma tears the thread of time, we do not live in the present — we live in a loop. The past reasserts itself. The future shrinks. And with it, our space — our internal room to move, imagine, and be — collapses.

To say that space is a consequence of time is to suggest that our mental space — the felt sense of openness within — depends entirely on how we relate to time. When time feels dangerous, space becomes tight. When time feels broken, space becomes chaotic or numb. This is not just metaphor. It is the experience of the traumatised body and mind.

It’s like when a child who was once bitten by a dog still flinches every time they hear barking, even years later — even if the dog is small and friendly. Their body doesn’t know it’s safe now. The past is still happening inside them. Or it’s like Harry Potter waking with nightmares in the safety of Hogwarts, the echo of trauma still pulsing through him long after Voldemort has gone. The danger is over, but his nervous system hasn’t caught up. His sense of now has been hijacked by then.

Julian Barbour, in contrast to Rovelli, proposes something even more radical: that time itself is an illusion. In his book The End of Time (1999), Barbour argues that the universe is composed not of events unfolding in time, but of countless static “Nows” — complete and timeless arrangements of everything that exists. What we experience as time passing is, in his view, the brain stitching together a sequence of these still frames, like flipping through the pages of a cosmic photo album.

“What we call the flow of time is a mental illusion,” Barbour writes, “a reflection of our memory and the way our brains work.”

Barbour’s theory challenges one of our most basic instincts: the belief that we move through time. But if he is right, it opens a haunting psychological possibility: perhaps our deepest suffering is not about time moving too fast, or too slowly, or looping uncontrollably — but about being stuck in one unbearable now.

It’s like when a child who was once bitten by a dog still freezes at the sound of barking, even years later. Their body doesn’t respond to the present — it responds to a frozen memory that remains vivid, alive, and unchanged. They’re not simply recalling the event — they’re still in it.

Or like Harry Potter waking in the night, years after the war has ended, gripped by nightmares that return him to the battlefield. He knows he is safe. The world has moved on. But his body hasn’t. Part of him still lives in the pain. That particular Now never faded — it remains lodged in his nervous system, replaying as if nothing ever changed.

In this sense, trauma is not only a disruption of emotional regulation — it is a kind of temporal imprisonment. The self does not move. Time does not flow. There is only the unbearable presence of the past, disguised as the present.

The Core Difference:

- Carlo Rovelli believes time is more fundamental than space.

- → He sees the universe as a network of events and relationships over time, and suggests space emerges from temporal structure.

- Julian Barbour believes the opposite:

- → Time is an illusion, and only space exists, as a series of disconnected “nows”. We don’t move through time — our brains just string static snapshots together, like frames of a film.

Time is more fundamental than space

If we follow what Rovelli suggests, our experience of the present isn’t just passive observation — it’s a constructed perception, shaped by the brain and nervous system. When we feel safe and regulated, time flows naturally. But under emotional distress, that flow becomes disrupted.

Hence:

Trauma bends time backward

Trauma creates a sense of temporal collapse: the past invades the present. The brain doesn’t store traumatic memories like ordinary ones; instead, they remain vivid, sensory-based, and emotionally raw. The amygdala (fear centre) stays active, while the hippocampus (which timestamps events) is often impaired. So when a trigger arises, the body reacts as if the event is happening now — not then.

· “I know it’s over, but it still feels like I’m right back there.”

This reflects the cognitive dissonance between intellectual understanding (that the event is in the past) and emotional or somatic experience (where the body still feels unsafe).

· “Every time I hear a loud voice, I freeze — I feel like I’m a child again.”

Here, a present-day trigger activates a sensory and emotional memory, bypassing rational awareness and recasting the present as the past.

· “It’s like I’m watching it happen all over again, and I can’t stop it.”

This illustrates the reliving quality of trauma, where the memory is not simply recalled but re-experienced — often vividly, through images, bodily sensations, and emotional overwhelm.

We don’t remember trauma; we relive it.

A series of disconnected “nows”

If we extend Julian Barbour’s model to psychology, a new picture emerges: suffering is not just about time warping or accelerating — it’s about time stopping. The flow of experience ceases, and the person becomes trapped in one unchanging emotional snapshot. The world moves, but internally, they remain caught in a loop that doesn’t unfold.

Trauma freezes the Now

Rather than bending time backward, trauma — through Barbour’s lens — locks a person into the moment of impact. It’s not that the past keeps returning; it’s that the traumatic now never ended. It remains vivid, charged, and alive, as if preserved in the nervous system like a photograph too painful to look at but impossible to put away. The body and mind stay lodged in that singular frame, unable to move forward.

In therapy, clients often describe this frozen quality of trauma in stark, time-defying terms:

· “I don’t remember it — I live it, over and over.”

The experience does not arrive as a thought or a story. It erupts. Their body braces. The air thickens. The moment floods them again.

· “It’s like I’m stuck inside a scene that won’t let me out.”

This isn’t metaphor — it’s geography. The mind constructs a space, and the self remains confined there. Doors don’t open. Time doesn’t pass.

· “I can feel the same fear in my chest, the same smell, the same silence just before it happened.”

For the traumatised self, details do not fade. They remain suspended — unchanged, unintegrated — waiting for a release that doesn’t come.

This is not remembrance. It is residence. Trauma is not something that happened once. It is something that continues to happen, precisely because the body has not yet found its way out of that particular frame of time. It is not the past returning; it is the present refusing to progress.

The trauma didn’t just happen. It’s still happening.

When Comes Before Where

And beyond both Rovelli and Barbour, emergent spacetime theorists remind us of something even more radical: that space itself may not be fundamental. What we perceive as location, direction, or boundary could be the surface pattern of deeper, more mysterious forces — information, entanglement, causality.

Physicist Fotini Markopoulou, for instance, envisions a universe in which causal relationships precede space — where “where” is less important than “when” and “why”. In this view, what matters most is not the geometry of things, but the logic of connection — the story that links one moment to another.

It’s like when a child who was once bitten by a dog still flinches every time they hear barking, even years later — even if they’re in a completely different place. It’s not the street or the sound alone that triggers them — it’s what that sound means. The fear isn’t tied to geography — it’s tied to the original sense of helplessness, to the why of the event.

Or it’s like Harry Potter waking with nightmares in the safety of Hogwarts, long after Voldemort has gone. The room has changed. The war is over. But the causal imprint of what happened — the betrayal, the loss, the burden — is still present. The danger isn’t in the location or time. It’s in the lingering why that hasn’t resolved. His nervous system is still entangled in the consequences of those events, mapping threat not by where he is, but by what was once true — and still feels active.

Seen through this lens, the human psyche might not be tethered to space at all, but shaped by relational time: by sequences of meaning, emotion, and memory. We do not simply exist in space; we are located in our past, in the people we’ve loved or feared, in the moments that shaped us.

Clients speak to this intuitively, often without knowing they are describing a causal, time-driven inner map:

- “I don’t feel safe anywhere, unless I’m with someone who understands me.”

- Safety, for this person, isn’t about physical surroundings. It’s about relational presence. Their sense of “place” is defined by who they’re with and when they feel seen.

- “Sometimes a smell or a word can take me back to a place I haven’t thought of in years — it’s like I’m instantly there again.”

- This is not about spatial travel. It’s about causal entanglement — how a small fragment of sensation reactivates an entire emotional scene, collapsing time and reconstructing a personal geography.

- “I can’t explain it, but I always feel like I’m on edge in that house. Nothing bad happened there… but it’s where everything changed.”

- “Where” is charged not by the room itself, but by its temporal meaning. The emotional map overrides the physical one.

In this way, emergent spacetime theory mirrors what therapists witness every day: that our lived experience of “here” is often dictated by “then.” That the psyche orients itself not through GPS but through stories, sensations, and symbolic threads of causality.

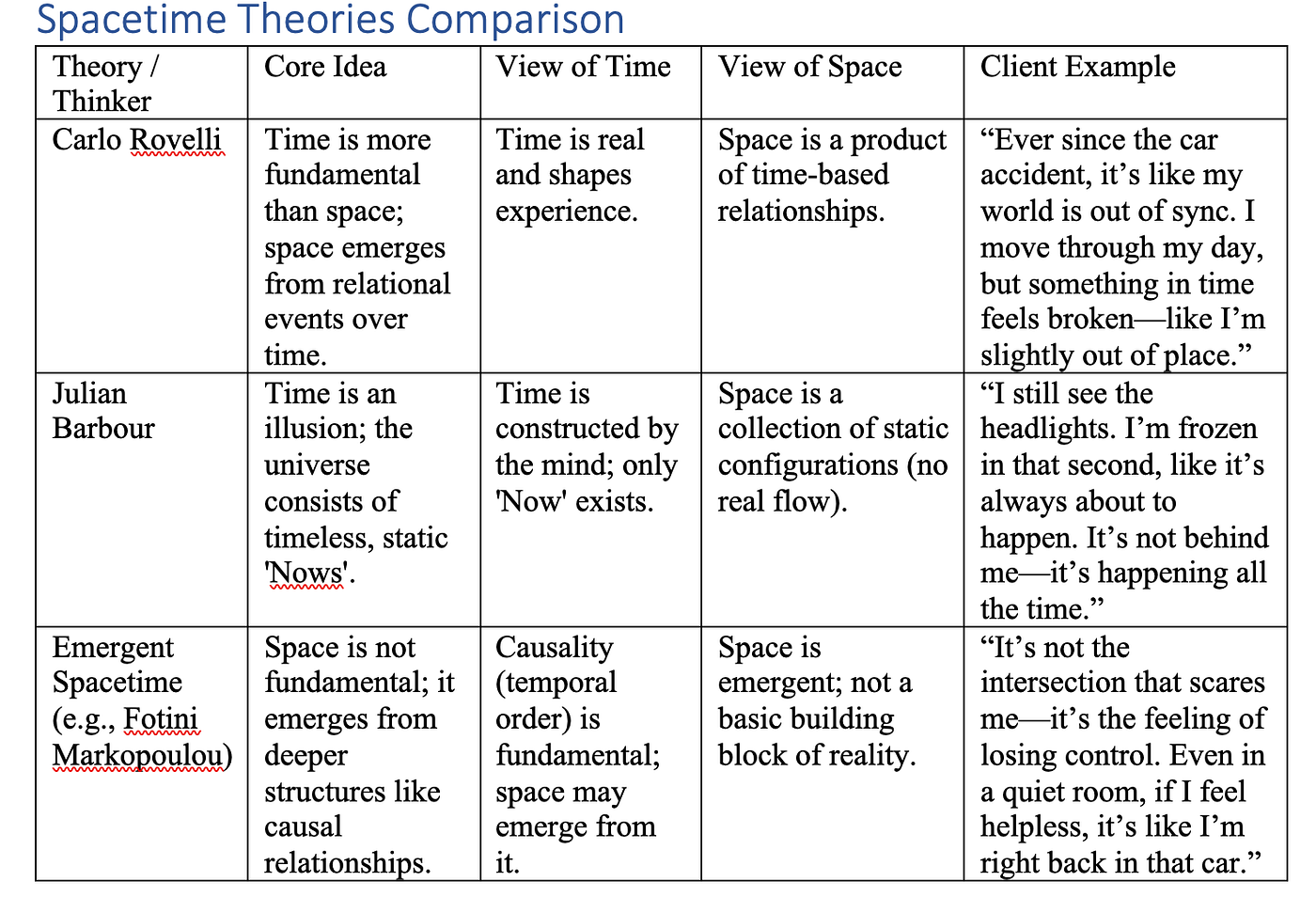

Spacetime Theories Comparison

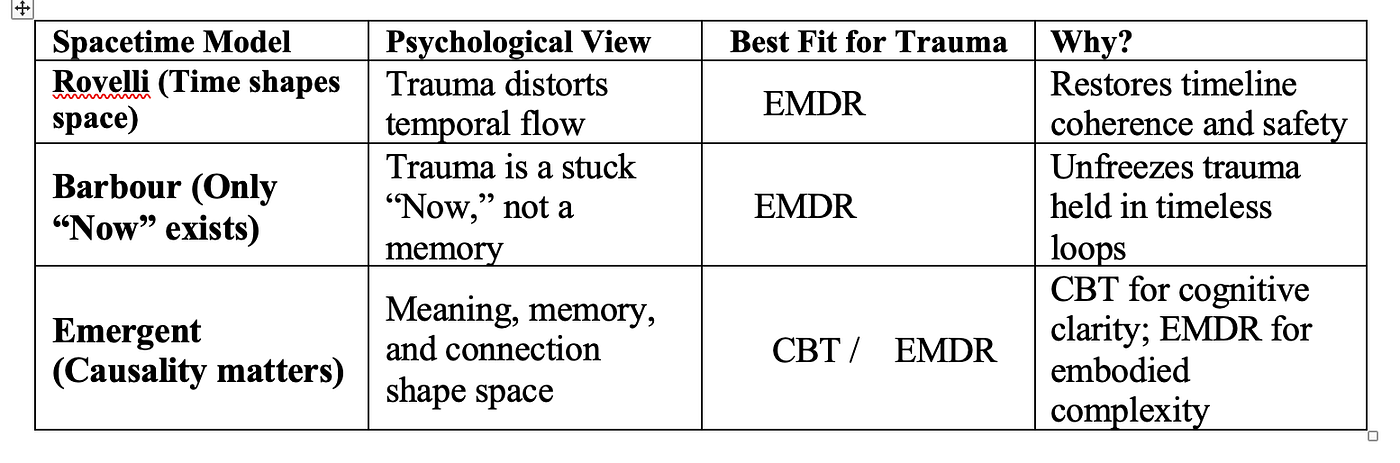

CBT or EMDR? Choosing the Right Therapy Through the Lens of Time

Let’s explore how each of the three spacetime models (Rovelli, Barbour, and Markopoulou/emergent spacetime) metaphorically supports either CBT or EMDR when treating trauma — and which therapy aligns best with each view.

🔹 1. Carlo Rovelli — Time as Primary; Space Emerges from Events

Psychologically: trauma distorts the flow of time, and that changes how we experience internal space.

Best Fit: EMDR

- Why? EMDR explicitly works with the flow of time — past, present, and future — by identifying unprocessed memories and allowing them to integrate through bilateral stimulation.

- EMDR aims to restore temporal coherence: helping the client feel that the event is truly over, rather than lingering in the present.

- Rovelli’s model supports the idea that when temporal flow is disrupted, internal experience (emotional space, self-perception) becomes distorted — just as we see in trauma.

✅ EMDR helps “reweave” the distorted timeline that trauma disrupts, making it a strong fit with Rovelli’s time-first framework.

🔹 2. Julian Barbour — Time Is an Illusion; Only “Nows” Exist

Psychologically: trauma is not a memory we revisit, but a “Now” we’re stuck in — eternal, unresolved.

Best Fit: EMDR (again), but CBT has limited usefulness here

- EMDR addresses trauma as frozen, emotionally charged “nows” that haven’t resolved. Barbour’s theory aligns with the felt timelessness of trauma: the event isn’t remembered, it’s relived.

- CBT relies more on linear thought restructuring — assuming that time and logic are intact enough to reframe beliefs. But if the client is trapped in a looped Now, this may not be accessible yet.

✅ EMDR’s non-verbal, memory-accessing method is better equipped to unfreeze these stuck moments and integrate them into a broader sense of self and time.

🔹 3. Emergent Spacetime — Space Emerges from Causality and Entanglement

Psychologically: our inner world is shaped more by “when” and “why” than “where.” Connection, meaning, and cause define our internal coordinates.

Best Fit: CBT or EMDR (depending on client)

- CBT can work well here, especially when helping clients explore causal meanings — “why did this affect me so deeply?”, “what story am I living through?”, “what keeps this belief alive?”

- EMDR also fits, especially when the trauma is tied to complex relational patterns or meaning-based wounds (e.g., shame, abandonment). EMDR can process entangled emotional memories and reorganise the client’s causal narrative.

✅ Both approaches are helpful here, but CBT may be more effective when the trauma is cognitively accessible and meaning-focused. EMDR shines when the trauma is felt but not yet understood.

Conclusion

EMDR is the most adaptable across all three models, especially when trauma is embodied, timeless, or resistant to rational analysis.

CBT is highly effective when the trauma is accessible through thought, especially when the client is able to identify and work with belief structures and causal narratives.

Client testimonials

Get in touch

Feel free to contact me if you have any questions about how therapy works, or to arrange an initial assessment appointment.

This enables us to discuss the reasons you are thinking of coming to therapy, whether it could be helpful for you and whether I am the right therapist to help.

All enquires are usually answered within 24 hours, and all contact is strictly confidential and uses secure phone and email services.

© Umberto Crisanti — powered by WebHealer