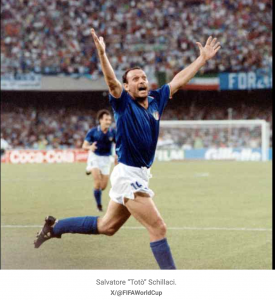

Footballer Totò Schillaci finds the back of the net once more, but this time in the hearts of his supporters. In testament to their love and esteem for him, many people in the city of Palermo queued up since yesterday afternoon (19/9/2024) to reach the funeral of the former national team striker, pouring out affection on his wife, children, and all his family members. “I hoped that all these people would come,” confesses Giovanni Schillaci, brother of the hero of Italia ’90. “Totò is a great man and he is receiving everything he deserved.” His wife added: “We are happy for the love from the people.”

From Humble Beginnings to National Hero

Totò Schillaci, born in a working-class neighbourhood of Palermo in Sicily, rose from humble origins to become one of Italy’s most beloved football legends. His meteoric rise to fame culminated in the 1990 World Cup, where his determination and skill captured the hearts of a nation. Despite facing public scrutiny and the pressures of life in the spotlight, Schillaci eventually earned admiration for his hard work and resilience.

The Lottery and Bias of Birth

Schillaci didn’t choose to be born into a part of Italy that was often looked down upon because of poverty, crime, and violence. He didn’t choose his accent or the context of his upbringing, yet he was judged for them. So much of our lives are shaped by factors beyond our control. We don’t get to choose where we’re born, our family, or our circumstances, yet we’re often judged as if those things define who we are.

For the former footballer, being heavily judged quickly became routine, as he recalls:

The ’90s in Palermo were terrible. I opened my eyes late. I thought only about playing, for me the mafia was just a local reality. Extortion, match-fixing, illegal gambling. Until one evening, during a retreat, Trapattoni [a legendary Italian football manager and former player] came up to me and said: “You’ve killed Falcone too.” [Falcone refers to Giovanni Falcone, a prominent Italian judge assassinated by the Mafia in 1992 for his work against organised crime.] ‘I replied: “Coach, I was with Baggio, ask him what I did.”’ [Baggio refers to Roberto Baggio, one of the most legendary Italian footballers, known for his exceptional skills and influence in the game]. Although it seems absurd to provide an alibi in this way, Schillaci commented ‘He wasn’t joking; the atmosphere was tense. But I went on to repeat to him when I left Juventus: “I didn’t kill him, nor did those Sicilians who don’t deserve prejudice.”’

Trapattoni’s remark about Schillaci and the Mafia-related murder of Falcone is a clear example of stereotyping and association bias.

System 1 and System 2

According to Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman, our brains process information in two distinct ways: System 1 and System 2.

System 1 is fast, automatic, emotional, and subconscious. System 2, on the other hand, is slow, effortful, and conscious. It’s almost as if we’re wired with a pre-reflective instinct, ready to react in fight-or-flight mode, driven by survival. When we encounter someone different — someone like Schillaci, with his southern accent or working-class background — our System 1 often takes over. We judge quickly and emotionally, without fully understanding the person in front of us.

These cognitive biases — like ingroup bias (where we favour people similar to ourselves) and confirmation bias (where we only see what fits our pre-existing beliefs) — shaped the way Schillaci was perceived. People in the North of Italy saw him through the lens of their biases, focusing on his accent, his origins, and using these as markers to define his worth. These biases are deeply human, but they limit our ability to see people for who they really are.

This ties into the lottery of life, a concept discussed by philosophers like John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. We are born into circumstances we didn’t choose, shaped by factors like birth, culture, and society. Jim Morrison famously captured this feeling in one of his songs when he sang, “Into this house we’re born, into this world we’re thrown.” Heidegger referred to this as “thrownness” — the idea that we are thrust into life without control over where we start, left to navigate the randomness of our existence.

The concept of “thrownness” and the lottery of life are tragically described by the genius of Dostoevsky through one of his characters, Ivan Karamazov in The Brothers Karamazov: “I am trying to find out where your God is just to return to him the entrance ticket — the entrance ticket to life. I don’t want to be here. And if there is any God, he must be very violent and cruel,” the character says. “Because without asking me, he has thrown me into life. It has never been my choice. Why am I alive without choosing it?”. Schillaci did not return the ticket, nobody can. Life is then inherited rather than chosen. We are judged but we don’t choose. Schillaci’s story — it’s ours too. I remember working with a client who had been bullied for her accent. When I asked her, “Where is this lovely accent from?” it was a relief for her to hear it framed as something positive, not something to be ashamed of.

Thus people come to therapy because they want to change their accents, believing that doing so will make them more accepted. But what does this say about the pressure we feel to conform to the world’s expectations? I hope that by keeping my own Italian accent (and by the way, I am not in control of this either), I can send a message that it’s okay to hold on to the parts of ourselves that make us unique. The problem isn’t in our accents or what we still carry with us from our backgrounds — it’s in the lack of acceptance we often feel from others.

“People are just as wonderful as sunsets if you let them be. When I look at a sunset, I don’t find myself saying, “Soften the orange a bit on the right hand corner.” I don’t try to control a sunset. I watch with awe as it unfolds.”

― Carl R. Rogers, A Way of Being

Many people find themselves in therapy stuck between who they are and who they think they should be. There’s often an internal conflict between what society expects and who we truly are. The struggle is not to change ourselves to meet those expectations but to learn to accept who we are, even in a world that constantly tells us we should be different.

Schillaci’s story isn’t just about football — it’s about the emotional pain of living on the margins, constantly feeling like you’re buffering, searching for connection in a world that doesn’t offer it. His celebrations after scoring goals — running toward hostile crowds, fists raised — weren’t acts of defiance or anger. They were pleas for recognition, for dignity. He wasn’t asking to be celebrated as a hero; he just wanted to be seen as worthy of respect. And isn’t that what we all seek? To be valued, not just for what we achieve, but for who we are? This is as he recalls these moments:

‘I brought my torment onto the field. Gossip, malice. They insulted me in the stadiums. It wasn’t enough to call me a ‘southerner’ and a ‘mafioso’; the chant ‘tire thief’ wasn’t enough either. No: they even called me ‘cuckold.’

Public shaming and insults almost certainly contribute to chronic stress and emotional suffering, often impacting a person’s sense of identity and mental health. Many clients report that emotional pain manifests in physical symptoms and behaviours. In this case, the torment carried onto the field likely reflects deeper unresolved inner pain. It’s highly probable that the audience’s barbaric behaviour traumatised him. People, especially those in the public eye, often suppress or numb their emotional responses to cope with pressure, which can further detach them from their authentic feelings and worsen psychological distress.

Respect was something Schillaci rarely received. Even at the height of his success, the scars of poverty and exclusion stayed with him. This wasn’t because of any failure on his part, but because society was quick to judge. Many people, particularly those who have been bullied, wrestle with the question: Why did they do this to me? Bullying often stems from people’s insecurities, fears, and need to assert dominance. When we see someone who seems different — whether in accent, background, or behaviour — I think System 1 kicks in, not just on an individual level, but collectively. We react quickly, from a place of fear, bias, or power, without taking time to understand.

Although Daniel Kahneman didn’t specifically address a collective System 1, I believe there’s a kind of group mentality that works in the same way. When a group sees someone who doesn’t fit into its norms or expectations, a collective, automatic reaction — shaped by cognitive biases — takes over, reinforcing judgments and exclusions. The herd mentality (or bandwagon effect) drives individuals to conform to group behaviours without critically questioning them, simply because ‘everyone else is doing it.’ This leads to groupthink, where the desire for group harmony causes people to overlook their moral concerns and blindly follow the crowd.

These biases also fuel confirmation bias, where the group selectively notices and remembers behaviours that confirm their negative judgments about the ‘other,’ while ignoring evidence that might challenge these views. Additionally, in-group vs. out-group bias further reinforces exclusion, as the group favours those within their circle and sees those outside of it as less deserving or even threatening.

In such environments, everyone feels the need to conform because others are doing the same, perpetuating a cycle of judgment and exclusion. Bullying often thrives under these conditions, where people act without reflection, driven by instinctive fear and these unconscious biases. Something about the herd mentality, the primal need to belong and not be left outside the group, keeps us stuck in System 1 (quick judgement), unable to evolve into System 2 thinking (evaluating with our own minds, using rationality and empathy).

Understanding these cognitive biases helps us start to answer the painful question of why. Bullies, whether individual or collective, act out of their own unresolved fears, traumas, and insecurities. Their actions are not a reflection of the person they target, but of their own need to feel powerful or accepted within the group.

So, how can we become better human beings?

I don’t know how one truly becomes a better human being, but I do know that we are conditioned from birth by society, culture, family, and experiences. This conditioning distorts our perception of reality, and it’s deeply ingrained in our System 1 thinking. We often find ourselves trapped in ignorance and habitual reactions. So, can we look at ourselves without the lens of this conditioning? Can we observe, without judgment, how we respond to life? This, I believe, is a crucial starting point.

Please forgive us, Schillaci, for we were acting from an underdeveloped System 2, relying too heavily on our automatic, biased responses from System 1. We failed to engage the deeper, reflective thinking that would have allowed us to see you for who you really were.

We see you now, or we try to - thank you.