I felt embarrassed. In the middle of my presentation, I had the sudden urge to turn to the audience, full of therapists, and ask: “But if a client says, ‘Why am I not my thoughts?’ or ‘What does that even mean?’ — what would you say?” Silence. Not the comfortable kind, but the kind that exposes the gaps we’d rather not face. It was as if, in that moment, we all realised we’d been trained to repeat these phrases without fully grasping them ourselves.

Later, while I was providing supervision, the same scenario unfolded. A supervisee hesitated when faced with the same question, and again, I saw the disconnect. Then, in a therapy session, a client told me, “I read online that I’m not my thoughts.” They wanted more than a cliché - they wanted substance. And that’s why I believe we need articles that nourish understanding - like our daily cuppa.

And that’s why I’m writing this. To offer depth, clarity, and a perspective that goes beyond the surface.

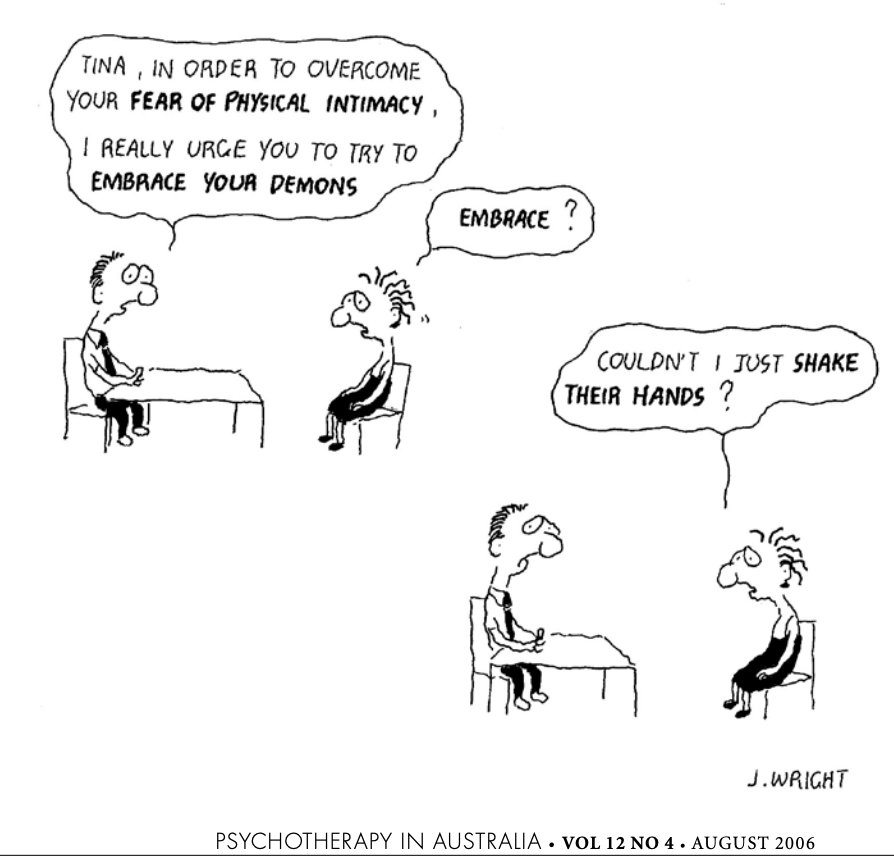

When the article Embracing Your Demons: An Overview of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy by Dr. Russell Harris was released, it felt like a breath of fresh air, a relief from the traditional “change your thoughts” approach in CBT.

Read the full article here: https://www.actmindfully.com.au/upimages/Dr_Russ_Harris_-_A_Non-technical_Overview_of_ACT.pdf

Dr. Harris shifted the focus towards accepting thoughts with ACT, a branch of CBT that encourages a different kind of relationship with the mind. Initially, I thought it was manna from the heaven. But as I introduced it to clients, I realised they needed more clarity. Many of them became even more confused, asking, “Am I supposed to accept my thoughts with ACT or change them with CBT?

Clearly, talking about thoughts requires careful introduction and guidance.

I’ve collected several questions from clients, which I’d like to clarify here.

Is it true that I am not my thoughts? (Preparation ad readiness)

Imagine someone casually tells you, “The solution is 15.” Your first reaction is likely, “What does that even mean?” That’s often how people feel when a CBT therapist says, “You are not your thoughts.” It’s a powerful idea, but without context, it feels abstract, like a riddle with no roadmap.

“You are not your thoughts” is actually a gradual process, not a quick revelation. It’s a teaching originally rooted in Buddhism, where monks would meditate for years to reach that understanding. Even the Buddha himself did not promptly reveal his discoveries; instead, he waited until a disciple was ready to comprehend and embody them. But these days, with the internet and ‘Dr. Google’, profound ideas like these are often handed out without preparation, making them harder to grasp and put into practice.

CBT adapted it, backed it up with research, and then presented it as a tool in therapy. But here’s the catch: simply saying it isn’t enough. It’s like giving someone a Ferrari without teaching them how to drive: powerful, yes, but without the right skills, it could even be dangerous.

Think of it like a math equation:

(3×4)+(18÷6)=15

You wouldn’t just jump to the answer. You can’t, can you? You’d need to break it down step by step, making sense of each part.

- First, you’d tackle (3×4)=12

- Then, you’d handle (18÷6)=3

Finally, you’d add the results:

3. 12+3=15

Step by step, you get to “15.” Simple, right? But without breaking it down, “15” on its own doesn’t mean much. And you already need to know addition and division; it’s not just calculation — there’s some prior preparation involved, isn’t there?

In the same way, understanding “you are not your thoughts” needs more than just hearing the phrase; it requires context, patience, and the right skills to unpack it.

Now, given that you were told ‘you are not your thoughts’ — or, in other words, ‘15’ — without preparation, let’s try to fill in some of the gaps

I think for us Western people, it’s better and easier to start with Heidegger and the concept of ‘Thrownness’. Don’t let Heidegger’s name intimidate you — I’ll keep it simple. If you haven’t come across it before, the idea of ‘Thrownness’ is simply about finding ourselves in a world we didn’t choose. As an example, let’s take Esty Shapiro, the protagonist in Deborah Feldman’s memoir Unorthodox, who captures this very sense of “Thrownness.” Esty’s story brings to life what it feels like to be born into a world where so much is already decided for you. Esty is born into a strict Hasidic community in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where she faces immense challenges. Unorthodox vividly captures the rigid rules and expectations imposed on her from a young age, revealing the intense pressure to conform to religious and cultural norms.

Esty’s journey is a testament to the human spirit’s quest for freedom, illustrating our potential to transcend the constraints imposed by our upbringing. This journey reflects the universal struggle many face when trying to break free from the limitations of their own life circumstances. As she grows, she realises that many facets of her identity are pre-set: our genetics, ethnicity, and social class, and so on. We grapple with the cultural, historical, or political forces that shape us, including our gender identity and the prejudices she faces.

How is this connected to “I am not my thoughts”? So, you want to master the idea that you are not your thoughts, and you’re already ready to jump straight to “15”? Wait - it’s a process. I’m here to help fill in some of the gaps along the way.

Her “Thrownness” — her background, religion, family, and social status — shapes her thoughts, her identity, and the paths available to her in life. In simple terms, every child is like a sponge, absorbing and storing all the information and energy around them, even before they can consciously understand these experiences. Every child is a silent witness to the tension between their parents, the arguments, stability, worries, and pressures. Does the child feel like a burden to their parents? Are they truly wanted? These experiences are imprinted as raw, unintegrated thoughts, perceptions, beliefs, ideas, emotions, physical sensations, and behavioural responses. Some of these stored experiences will become vulnerabilities, wounds, traumas, or enduring thoughts.

Let’s have a look at her thoughts, followed by the underlying process:

- “Why does everyone seem so certain, while I feel so lost?” (Confusion and Doubt)

Esty questions her place in a community that seems unwavering in its beliefs, feeling isolated in her uncertainty. - “What if people find out that I’m different?” (Fear of Judgment)

Her fear of being seen as an outsider reflects the deep pressure to conform and fit in, no matter the cost to her individuality. - “Is this really who I am? Or is this just who I’ve been told to be?” (Identity Crisis)

Esty starts to wonder if her sense of self is truly hers or just an identity shaped by her surroundings and expectations. - “There must be something more than this life.” (Desire for Freedom)

This thought reflects her inner spark, a yearning to explore a life beyond the strict boundaries of her upbringing. - “I am not enough as I am.” (Sense of Inadequacy)

The community’s rigid expectations make her feel inherently lacking, as though she can never be truly worthy on her own terms. - “Is it wrong to want something different?” (Curiosity and Guilt)

Esty’s curiosity about life outside is laced with guilt, as she questions whether it’s wrong to desire a different path.

Now imagine Esty goes to a male therapist from the same Hasidic community, and he says to her, “Come on, Esty, you are not your thoughts.” Do you understand now? What would happen here? He is missing the point entirely!

This phrase is not a shortcut, and it cannot be handed over like a prescription!

I am not my thoughts or can you help me change my negative thoughts?

I often follow up by asking, “What are the ‘negative’ thoughts we’re talking about?” For instance, clients might share, something like “I have this thought that I’m gay.”

First, I think it is reasonable to ask something along the lines of, “Let’s explore what this thought means to you and where these feelings come from. Can you tell me more about why it feels negative or troubling to you?” Here, I often encounter resistance from people:

“Oh but I have SO-OCD, I am not sure you heard of this? It is a Sexual Orientation Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, I am straight and I have ‘gay thoughts’. I don’t want to have sex with women (or men). But I think about them constantly.”

Some people approach therapy with an ‘out with the bad, in with the good’ mindset (Hayes et al., 1999), treating thoughts as if they were files on a computer — something to be deleted and replaced. Maybe we’ve been a bit too enthusiastic and compared the mind to a computer a bit too much in recent times, and the metaphor doesn’t really hold. This mechanistic view, where thoughts are simply exchanged, contrasts sharply with a contextual approach. Instead of rejecting or replacing negative thoughts, the focus shifts to ‘seeing the bad thought as a thought, no more, no less’ (Hayes et al., 1999).

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy. New York: Guilford Press.

Secondly, who told you it’s a negative thought?

Let’s consider what we mean by a “negative” thought. When we label a thought this way, we’re engaging in interpretation, a judgement layered over basic neurological activity. Thoughts, in their raw form, are simply patterns of neural firings. These firings don’t carry inherent meaning; it’s our interpretation that gives them symbolic weight. As Epictetus wisely noted, “What really frightens and dismays us is not external events themselves, but the way in which we think about them. It is not things that disturb us, but our interpretation of their significance.” This insight lies at the core of CBT: it’s not the thoughts themselves that hold power but how we choose to interpret and react to them.

I want to emphasise that these thoughts do not necessarily signify a different orientation (though they might in some cases) but rather may reflect areas where the person is struggling with acceptance, self-concept, and authenticity. By accepting these thoughts without judgement, their power diminishes, and distress lessens. Gentle self-enquiry can help to explore these inner conflicts with compassion and curiosity. This shift allows clients to observe their thoughts without judgement, fostering a more accepting and transformative relationship with their inner experience.

And now, a question to close: why are some people so preoccupied with this idea of ‘Am I my thoughts?’ From my observations, the answer lies in control. Some people are deeply afraid of their inner life — thoughts, emotions, behaviours, and even their own body. If they could control their heartbeat, they would. This intense need for control is often a strategy to numb their fear or anxiety. But here’s the paradox: thoughts are automatic, and the more you try to control them, the more they seem to take over. It’s in letting go of that control that true peace can emerge.