Rats, Pigeons, The Duolingo Owl, and Streak

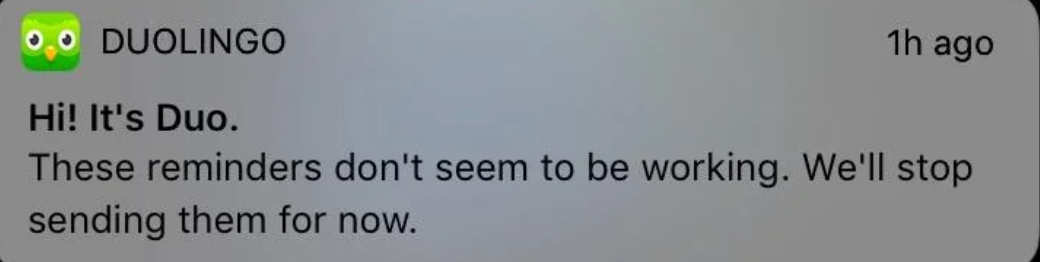

The notifications were particularly unsettling. They seemed emotionally manipulative, especially when they focused on maintaining my streak.

Sometimes I’d receive messages like, “These reminders don’t seem to be working. We’ll stop sending them for now.”

This tactic made me feel guilty for not practising. It wasn’t about genuine motivation anymore, but about avoiding that uncomfortable feeling of letting myself — and apparently the app — down.

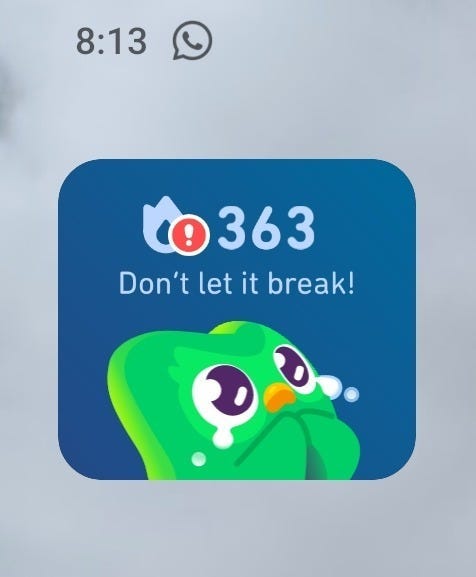

This experience reminded me of classical conditioning, like Pavlov’s dog and Skinner’s rats. Duolingo used similar techniques. Just as Pavlov’s dogs linked the sound of a bell to getting food, I started to link finishing my lessons with the reward of keeping my streak. It became less about the joy of learning and more about holding onto that streak

Duolingo also uses negative reinforcement, a concept deeply explored by B.F. Skinner in his work on operant conditioning. Negative reinforcement involves removing an unpleasant consequence to strengthen a behaviour. In this case, the fear of losing my progress — the potential loss of my streak — acted as that unpleasant consequence. To address this, Duolingo introduced “Streak Freezes,” which allowed me to avoid losing my streak even if I missed a day. This feature only reinforced the habit further, as it reduced the anxiety of failure without changing the underlying motivation. I wasn’t learning because I enjoyed it anymore; I was driven by the need to protect what I had built, avoiding the negative feeling of loss

In reflecting on my experience, I am sure that B.F. Skinner and Daniel Kahneman, the author of Thinking, Fast and Slow, would agree that other psychological mechanisms were at play, such as variable rewards and loss aversion, which kept me hooked.

Variable rewards is a concept Skinner would most likely discuss. He explored how unpredictable rewards can create powerful behavioural conditioning. In his experiments with rats and pigeons, Skinner showed that behaviours reinforced by unpredictable rewards tend to be more persistent than those with consistent rewards. This is because the unpredictability makes the reward feel more exciting and worth pursuing. In Duolingo, this is reflected through surprise rewards like extra points or bonus exercises, keeping users hooked by making the experience feel fresh and engaging.

Loss aversion, on the other hand, is tied to the work of Daniel Kahneman, a Nobel Prize-winning psychologist. Along with Amos Tversky, Kahneman explored how people are more motivated to avoid losses than to seek equivalent gains. This idea is a core principle of behavioural economics, and it explains why I was so driven to protect my streak on Duolingo. The fear of losing something I had built up, even if it wasn’t tangible, was stronger than the desire to keep learning for the joy of it.

Loss aversion is also strengthened by another tactic: urgency. We don’t want to miss out or regret not taking action, so we rush to complete the task. This strategy, called scarcity, taps into our fear of missing out and motivates us to act quickly, even if it’s something we weren’t originally excited to do. This is often used in marketing and apps to keep us engaged

or

But you have a good friend, they are likely to respond with understanding and empathy when you need to cancel a meeting for a lesson. They won’t make you feel guilty or pressured to reschedule right away. Instead, they’ll give you space to take care of yourself and offer flexibility for when things calm down. Do you notice any difference compared to Duo?

The app’s social features, like leaderboards, added a competitive element, pushing me to stay engaged, not for my own improvement, but to stay ahead of others.

Personifying the app was the most emotionally manipulative tactic. Messages like “Duo is sad you missed a day” tugged at my emotions, as if I was letting down a friend instead of missing a day of language practice.

Reflecting on all of this, I began to wonder if this was really the best way to learn. In France, I had the chance to practise in real-world settings, to talk with people, listen to the local radio, and read newspapers. Those interactions, though imperfect, felt far more meaningful than ticking off another day on the app. Language is, after all, about communication — about connecting with other human beings, not just reaching milestones on a screen.

Yeah, you could argue, “Mate, you don’t live in France, and you’ll eventually return to England,” or “We don’t know any French people where we live, or the language we’re learning, and we can’t afford private tuition.” Touché! It’s free, I get that. But I believe there are alternative ways to learn that don’t rely on streaks, competition, or guilt, and that encourage human connection — and are fun.

Ultimately, learning should be about joy, curiosity, and personal growth, not about streaks or rankings. As Albert Einstein once said, “Education is not the learning of facts, but the training of the mind to think.” Let’s not forget why we start learning in the first place — to grow, explore, and expand our horizons, not to tick off a box each day. In the end, isn’t it about connecting and communicating with others? Sharing experiences and gaining a deeper understanding of the world?

Bien sûr, you might proudly say, “With each day, I add to my streak — I feel more accomplished.” But have you ever wondered what part of you it takes away? Your streak adds structure, but does it also take away the joy and purpose from your learning?